From Ancient Greece to HS223: Inside the scramble for recommendation letters

Students and faculty work together for college acceptances

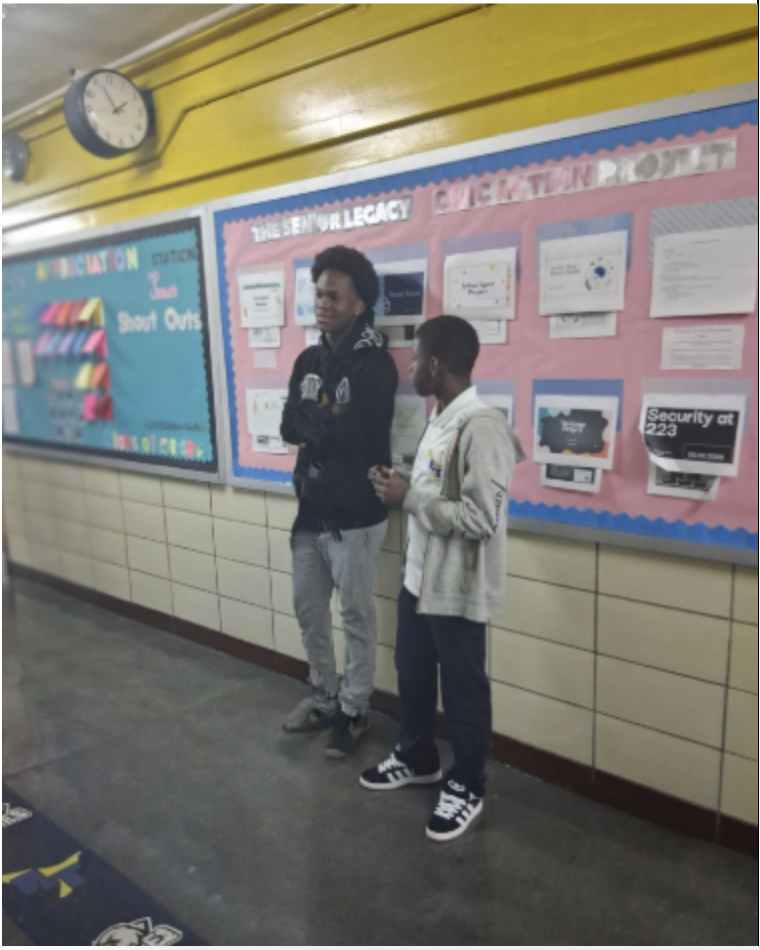

College banners in the second floor hallway at HS223 (Photo by Jason Garcia)

Don’t be shy about asking a teacher to write you a college recommendation letter. Do ask early, the sooner the better — as in, like, six weeks before the college’s deadline. But don’t expect a great recommendation if you’ve slacked off in that teacher’s class.

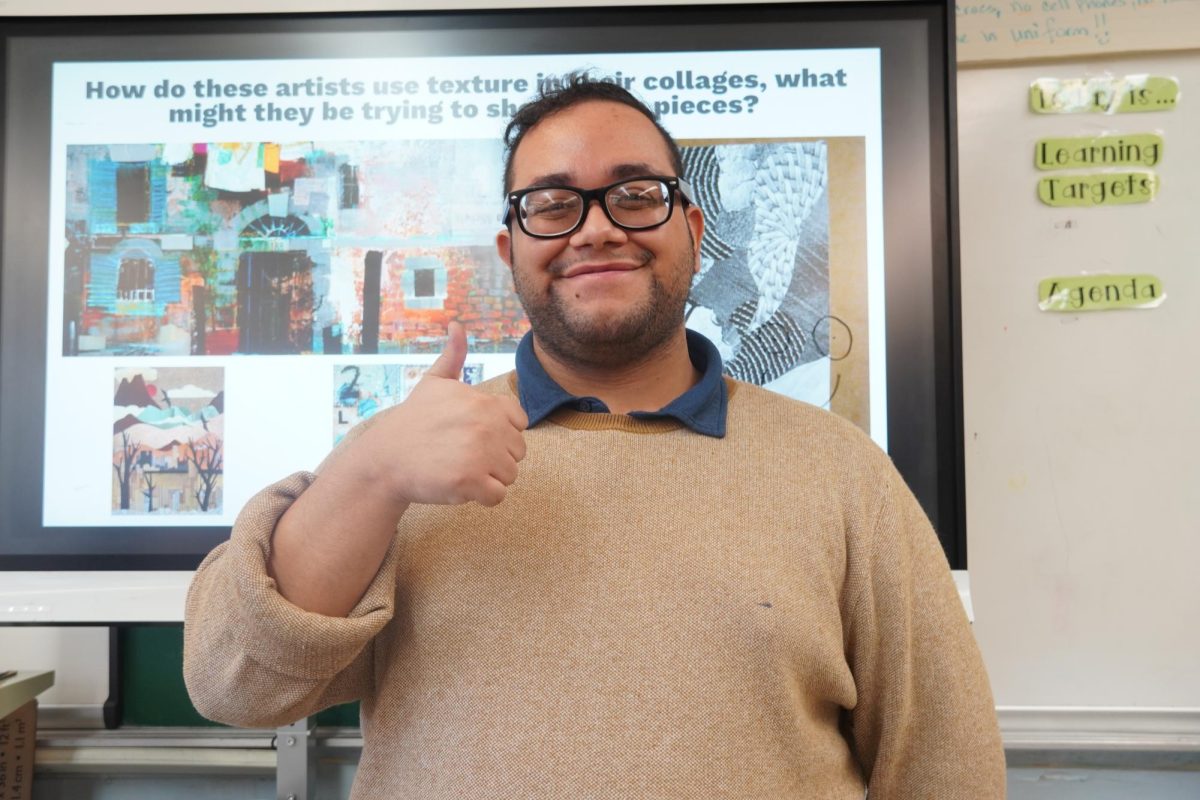

That’s some of the advice from veterans of the recommendation letter process. Laboratory School of Finance and Technology teacher Mr. Ohl, for instance, says he relishes writing the letters to highlight students’ best qualities.

But no faculty member is a miracle worker.

“If you don’t really try in school, it makes it hard to write a recommendation letter for you,” said Mr. Ohl, who estimates that he writes six recommendations each year. “Having a good recommendation requires the student to try their hardest in school.”

The race to secure recommendation letters — the genre has roots that date back to Ancient Greece, according to the American Historical Association — comes as HS223’s 100 or so seniors begin this fall to undertake the college application process. Between 85% and 90% of seniors request at least one recommendation letter, according to Ms. Gomez, one of the school’s college counselors. Additionally, she said, between 180 and 190 recommendation letters from the faculty are written each year for seniors. On average, each student gets two recommendations.

Recommendations have different due dates, depending on the college. Early decision requires recommendations to be submitted in early to mid November, while letters for the regular application process must be submitted by mid to late December.

A teacher who knows his student

Senior Juan Morales is applying to college under the regular process. And when the time comes this month for him to seek out his recommendation letters, the first teacher he’ll ask is someone who has taught him since his first day of high school — Mr. De Jesus, an English teacher.

“I can trust Mr. De Jesus because he’s the only teacher that taught me both in middle school and in high school,” Morales said, adding: “Since I had him in 8th grade, and now I have him again in 12th grade, he can see the changes and growth that I made throughout the years.”

Mr. De Jesus recalled the potential he saw in Morales early on and how he’s matured over those four years.

“In the 8th Grade, Juan was very consistent with his independent reading and writing notebook. He certainly shared a great interest in literacy,” Mr. De Jesus said. “He was always very timid, and usually socialized with his small group of friends or when asked to participate in class.”

Morales said that Mr. De Jesus is the right recommender because he’s seen Juan grow less introverted.

“I think I improved my communication skills because in middle school, I was shy to talk to people. But now, I’m not really that shy anymore,” Morales said.

Senior Zarwane Toure said he still hasn’t decided whom he’ll ask for a recommendation letter. But whomever he picks, he says, he’ll seek out someone who can speak about the work he’s put in throughout high school.

“Teachers see the different ‘faces’ of a student while they’re in a classroom and the way they grow and develop. Since they spend so much time with us, that gives them somewhat of an authority to talk about what makes a student great and awesome,” Toure said by text.

Thousands of years old

What we would recognize these days as the recommendation letter traces its roots back to Ancient Greece. The genre had gained a foothold by Roman times by the era of the statesman Cicero, and were used for younger clients seeking favors from new patrons, according to the American Historical Association article.

In modern times, the letters have unsavory roots, according to an article in the news outlet Inside Higher Ed: in the early part of the 20th century, colleges like Harvard, Princeton and Yale began to require the letters as part of a campaign to limit admission of marginalized groups, such as Black people, Catholics and especially Jews — in favor of White and rich Protestants.

Nowadays, colleges seek recommendation letters to flesh out an applicants’ talents beyond marks and test scores; to describe tangible examples of character and personality; and to discuss one’s relationships in the community, according to the College Board, a member organization of 6,000 educational institutions that administers the SAT and Advanced Placement exams.

What faculty think

Mr. Ohl, a founding member of HS223, has been writing letters of recommendation since the addition of a high school section in 2013.

“Some years it’s more, and some it’s less,” he said. “I like being able to use words to help promote a student to a college, university, or program. I also like thinking about what makes a student really stand out. Capturing their uniqueness is one of the joys of the activity.”

But it’s not as joyous when the process is rushed.

Sometimes, he lamented, students ask for a letter with just a week’s notice, so a letter isn’t as strong as it might otherwise be. Ideally, he says, he wants four to six weeks of lead time.

“My only pet peeves are being asked right before the due date and not having enough time to write properly,” he said.

Ms. Gomez is one of HS223’s five college counselors; she has been at the school since 2015 and worked with every senior class since the first graduating class of 2017. Counselors like Ms. Gomez not only help facilitate recommendations from faculty and recommenders outside HS223, but also correspond with students about college options, coordinate virtual information sessions and more.

She understands why students don’t always stick to deadlines, but she suggests students do their best to be punctual.

“They get overwhelmed because their schoolwork gets compiled, which makes them overlook and not allow them to research,” she said.

Ultimately, while faculty are there to help, students must be responsible for their own success in high school — and beyond.

“If you’re not invested, then the end result is really all on the student,” Ms. Gomez said. “I can’t want this more than the student does.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Laboratory School of Finance and Technology. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Jason is a member of the Class of '23 at The Laboratory School of Finance and Technology.

Phoebe M

Apr 18, 2023 at 12:33 pm

I really like your angle on this because I think recommendations are a significant part of the college process that, as a student journalist, I’ve noticed isn’t always reported on. It’s interesting how you also incorporated the history of recommendations, and how they previously have been used for discriminatory reasons. This is a great way to open the article to a topic bigger than just the initial idea and is a great method to use in your articles 🙂

Henry Watson

Apr 18, 2023 at 8:37 am

Dear Jason,

As a Sophomore student at another High School in CT, this article is nevertheless incredibly helpful and interesting– especially due to my grade level. Mr. Ohl’s advice for how to get a good recommendation is extremely valuable, and the statistics added to provide scale of the practice and its history was fascinating. I also never knew the darker side of recommendation letters, specifically, how they were used to limit minority groups for white protestants. The end advice by school counselor Mrs. Gomez was also great–it’s mainly up to us to decide how good we want our recommendation letters, and ultimately, college chances.

Look forward to reading more of your work!

Regards,

Henry

Henry Watson

Apr 17, 2023 at 3:11 pm

Dear Jason,

As a Sophomore student at another High School in CT, this article is nevertheless incredibly helpful and interesting– especially due to my grade level. Mr. Ohl’s advice for how to get a good recommendation is extremely valuable, and the statistics added to provide scale of the practice and its history was fascinating. I also never knew the darker side of recommendation letters, specifically, how they were used to limit minority groups for white protestants. The end advice by school counselor Mrs. Gomez was also great–it’s mainly up to us to decide how good we want our recommendation letters, and ultimately, college chances.

Look forward to reading more of your work!

Regards,

Henry

Tom

Nov 1, 2022 at 10:15 pm

Excellent article.