At The Laboratory School of Finance and Technology, the Performance Based Assessment Task (PBAT) system stands at the heart of our academic experience. Unlike schools that rely on standardized state tests, we demonstrate mastery through rigorous, project-based learning and presentations. While this model gives students a deeper opportunity to challenge themselves, many are starting to question whether the way PBATs are scheduled, especially in junior and senior years, is really setting us up for success.

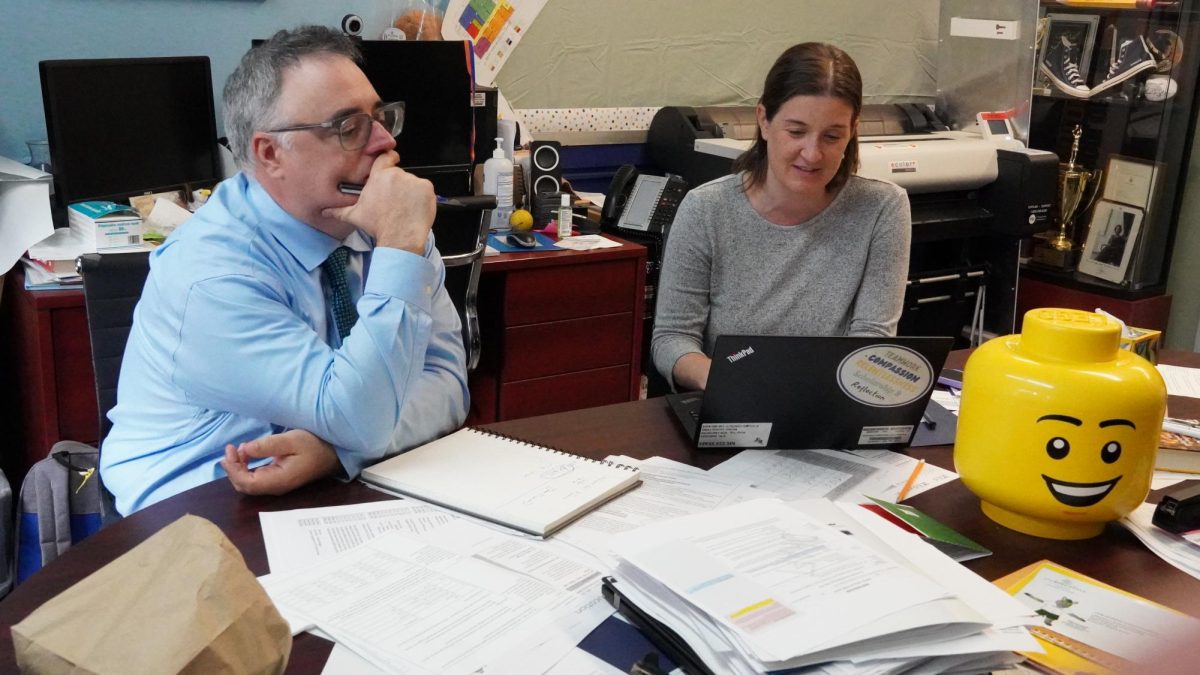

To better understand this, I interviewed Ms. Meyers, a 11th grade history teacher at our school, along with Yahaira, an 11th grader, and Kary, a 12th grader. Our conversations focused on two key questions: Is it fair for students to present PBATs during spring break? And should PBATs begin earlier in a student’s academic journey, such as in 10th grade?

Should PBATs Be Presented During Spring Break?

Ms. Meyers explained what many students feel but might not always say out loud: “I honestly don’t think it’s fair. I think students should have their spring break. We try to give them that time off. It’s preferable to schedule presentations on school days.” She emphasized that Spring Break is a time to rest, not just for students, but for teachers too.

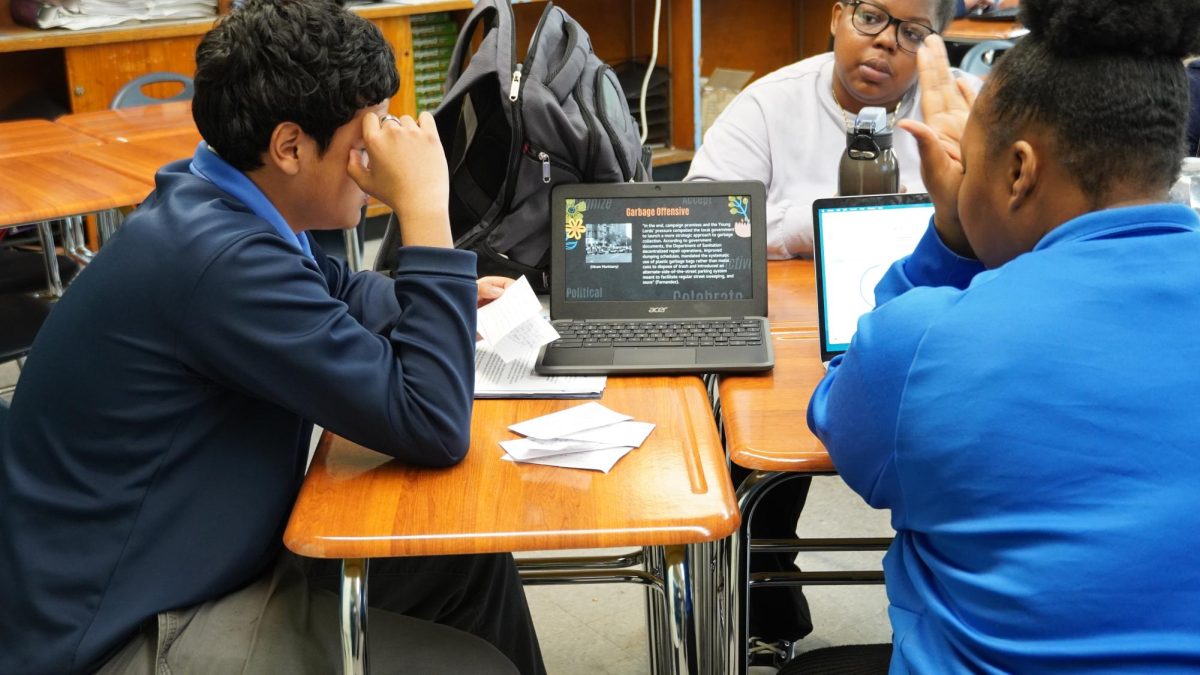

Yahaira, an 11th grader, explained how PBATs during break can cause stress not just academically, but emotionally.

“It’s not fair because some people have plans and PBAT presentations can interfere with those plans, leading to unnecessary chaos. It adds stress on both students and teachers—everyone deserves that mental break.”

Yahaira’s response reveals something deeper than just frustration with scheduling; it shows the growing issue of school-life balance. As students navigate academics, jobs, family responsibilities, and mental health, Spring break becomes one of the only true chances to recharge and mentally relax. When PBATs happen at that time, the lines between school and personal life become blurred, leading to burnout and stress, overwhelming the students.

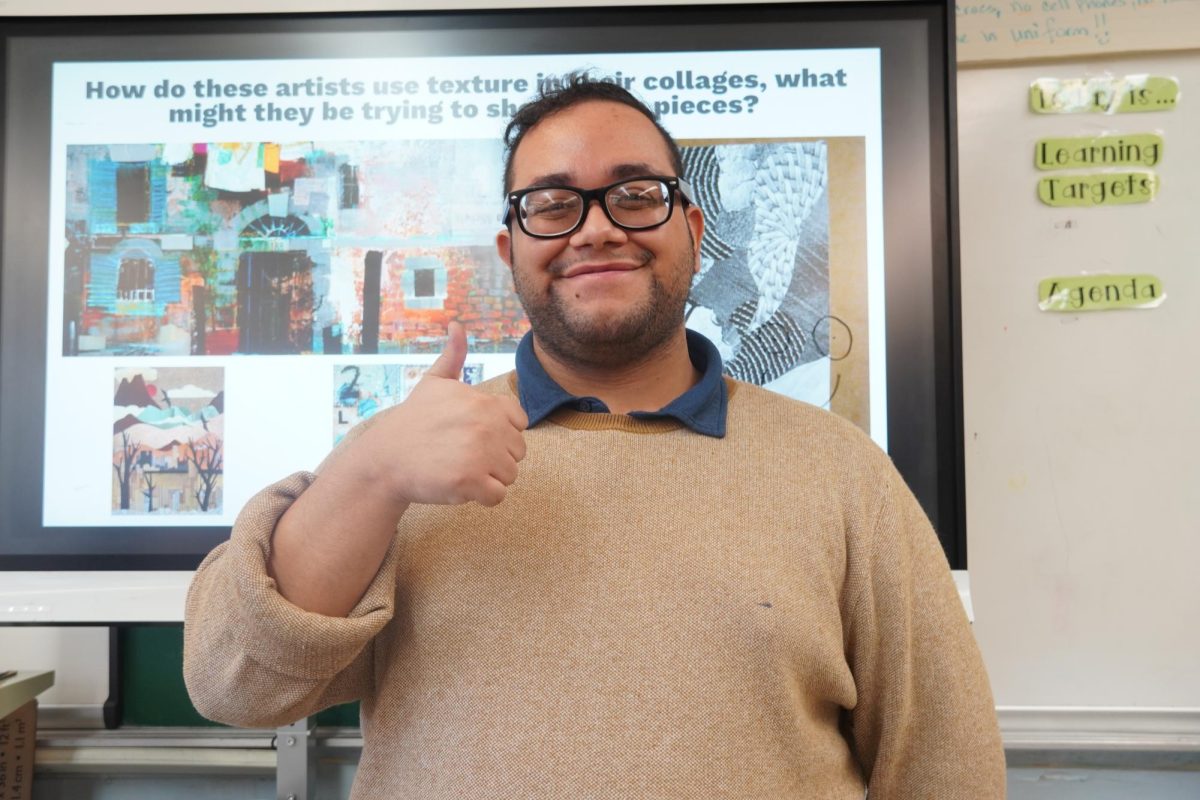

Kary or Abubakary Hydara, a senior who has already experienced the full weight of PBATs and still is, offered a more flexible opinion on this topic:

“I think it depends. If you were given enough time and you’re still behind, maybe it’s fair to come in during break. But if you were on track, then the teacher should find time during school.”

Kary’s point raises a good question about accountability vs. flexibility. Should all students be treated the same, regardless of effort and preparation? Or should there be more personalized accommodations based on each student’s progress? His answer suggests that fairness isn’t always equal treatment; it’s about understanding the context of each student and accommodating to each one of them in their need.

Should PBATs Start Earlier?

Currently, students typically begin their PBATs in 11th grade, but many including teachers are rethinking that timeline.

Ms. Meyers explained that although the school has considered starting earlier, they’re limited by rules set by the PBAT Consortium.

“We tried to introduce PBATs in 10th grade, but the group of schools we’re part of doesn’t allow it. Still, I think it’s possible. We could use 10th grade for pre-prep—teach the content and the big ideas early, so students aren’t overwhelmed when it’s time to do the real thing.”

Yahaira fully supports this idea:

“It would be better to start around the middle of 10th grade. That way, we’d have a year and a half to prepare. Senior year is already intense, and junior year is super stressful too. Sophomore year is usually easier—so why not start then?”

Yahaira’s comments highlight the academic pressure and uneven workload distribution. Right now, most students face a sharp learning curve when PBATs suddenly arrive in junior year just as many are adjusting to harder classes, SAT prep, and college planning. By beginning the process earlier, students could build skills gradually instead of being thrown into a turmoil of overwhelming stress.

Kary, reflecting on his own experience, added

“PBATs can get really stressful when they’re all packed into one year. If we spread them out, it would be less intense and more manageable.”

The Bigger Picture

What these conversations reveal is that PBATs, while valuable, need to be reimagined through the point of view of students’ experience. There’s a growing need to reconsider how we balance rigor with wellness, and how we prepare students to succeed in a healthy and relaxing way, and not just them completing assignments or doing the PBAT Work.

PBATs have the power to teach research, critical thinking, and public speaking skills that go far beyond a classroom. But for them to work as intended, the structure around them needs to adapt. More time, earlier exposure, and thoughtful scheduling could make a huge difference in helping students not only complete their PBATs but thrive while doing so.

If our school wants to support true learning, we need to start by listening to the students carrying the load and the teachers guiding them through it.